Social norm has it that people are expected to respond to mobile phone messages quickly. However, notifications may arrive to our mobile phones at any place and any time, which, depending on the concurrent activity, can be disruptive for the user. Hence, research has explored ways to reduce the chance of disrupting users by deferring the delivery of notifications until opportune moments.

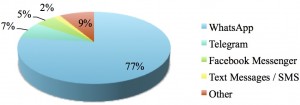

For most people, the majority of notifications come from messengers, such as WhatsApp or SMS. This type of communication goes along with high this type of communication social expectations. The majority of the people expect people with whom they frequently communicate to respond within a few minutes. Thus, deferral cannot be indefinite: it requires a bound, that is, a maximum delay before the notification is delivered, not matter how disrupting it might be.

For most people, the majority of notifications come from messengers, such as WhatsApp or SMS. This type of communication goes along with high this type of communication social expectations. The majority of the people expect people with whom they frequently communicate to respond within a few minutes. Thus, deferral cannot be indefinite: it requires a bound, that is, a maximum delay before the notification is delivered, not matter how disrupting it might be.

But, what is the right bound?

Social expectations suggest a few minutes maximum. However, how likely is it that an opportune moment occurs within 5 minutes?

We collected evidence regarding these questions in our work I’ll be there for you: Quantifying Attentiveness towards Mobile Messaging.

Over the course of two weeks, we collected more than 55,000 message notifications from 42 mobile phone users. On the basis of this data, we trained our previously described machine-learning model to predict attentiveness. This model uses sensor data from the phone to predict with close to 80% accuracy, whether a mobile phone user will attend to a message within 2 minutes or not.

We used this model to compute each participant’s predicted attentiveness for each minute of the study. In summary, our data shows that people are attentive to messages 12.1 hours of the day, attentiveness is higher during the week than on the weekend, and people are more attentive during the evening. When being inattentive, people return to attentive states within 1-5 minutes in the majority (75% quantile) of the cases.

Consequently, a bound of 5 minutes or less will ensure that bounded deferral strategies are likely to deliver messages in opportune moments, while reducing the likelihood to violate social expectations.

The results are presented at MobileHCI ’15: ACM International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services.

Tilman Dingler and Martin Pielot

I’ll be there for you: Quantifying Attentiveness towards Mobile Messaging

MobileHCI ’15: ACM International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services. 2015.